It was early spring as I travelled through Ayrshire, hugging the picturesque coastline on my journey south. As morning elapsed and afternoon commenced, my trail was intermittently bathed in bright afternoon sun, arriving in bursts between the continuously shifting clouds overhead. At the point of a momentary occlusion I diverted inland, following the lower course of the River Stinchar along a leafy country lane, drawing closer to my destination.

It was early spring as I travelled through Ayrshire, hugging the picturesque coastline on my journey south. As morning elapsed and afternoon commenced, my trail was intermittently bathed in bright afternoon sun, arriving in bursts between the continuously shifting clouds overhead. At the point of a momentary occlusion I diverted inland, following the lower course of the River Stinchar along a leafy country lane, drawing closer to my destination.

I grew alert; the anticipation of an impending sighting stirred within as I wended my way along the road, trying to discern the point where my map told me the ruin I sought would be positioned. A moment later and there it was, as expected. The bulky vertiginous block of Balnowlart House visible through branches newly burgeoned with buds.

I pulled in by a small white cottage set next to the road, so as to regard the ruin a little longer from this vantage point. It had more than just a trace of the typical haunted mansion about it, appearing gaunt and vacant up on the hillside. Noting the front door of the lodge to be open, I walked up the drive and knocked, my call being answered by a couple readying what was evidently a holiday let for its next visitors.

Being just a recent discovery of mine and a fairly spontaneous visit, I hadn’t conducted much research into Balnowlart’s history, and out of habit asked if I could photograph the ‘old house’. “Oh it’s not old,” came the reply, “it was only built in 1904.” My request was nevertheless met with agreement, and after being warned to watch my footing as few floors remained in the building I made my way up the track which led to this early 20th century ruin.

Nearing the house, I followed a rusted iron fence which bordered a patch of tall spindly trees, the bases of their trunks surrounded by new daffodils bursting through the dead winter scrub. The dark gable end of the house loomed through the trees, and as I followed the curved ascent of the path I rounded upon its entrance front.

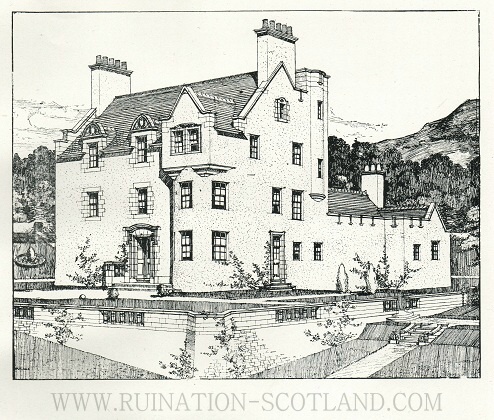

A perspective view of Balnowlart by its architects shows the house to marry its environment quite comfortably, bedded down in its hillside location with the aid of balustraded terraces and stepped pathways. However it seems that this landscaping never materialised; the house appearing in a historic photograph without such garden ornamentation. Even then, the house seemed somewhat marooned, not quite so successfully seated in its surroundings as envisaged. But the effect is only emphasised today by the rusting agricultural machinery which lies scattered around it.

I climbed the steep bank ahead and came face to face with Balnowlart’s southern façade. Sure enough, closer inspection revealed Balnowlart to be of more recent construction to the majority of ruins I’ve visited, despite its loose stylistic imitation of a much older fortified tower house.

This front was dominated by a full height bow topped with a cap house, the only notable projection from an otherwise stark oblong block of three storeys. Before me the front door stood open, just like the lodge on the roadside, though wedged ajar with a trickle of debris making it clear that nobody would be found at home here. Declining its invitation, I ventured instead on my customary tour of the exterior, circling the base of Balnowlart’s huge brooding walls.

Apart from the absent terraces, the scheme for Balnowlart seems to have been built more or less as planned to the designs of J. Jerdan & Son, an architectural practice responsible for the construction of numerous large villas in the Colinton suburb of Edinburgh. Balnowlart is featured in James Nicoll’s Domestic Architecture in Scotland of 1908, and in many ways seems fairly illustrative of this new period of design. This was a time when the range of available building materials was extending, allowing architects and builders to be a little more experimental in their compositions.

Nicoll is an advocate for the use of imported materials, eager to find alternatives to the “grey or brown stone and blue or purple slates [which] were the standard materials of the better class of self-contained houses” a few years previously. He argues against the widely adopted theory that “only those [materials] produced in the locality are fitting and will harmonize with the surroundings”, instead exalting the virtues of rough cast, which “properly used will assimilate unobtrusively with the peculiarities of style of practicality and locality.”

I couldn’t say the effect of Balnowlart’s own render was quite as agreeable as I surveyed its rough texture, the re-emergence of the sun doing little to lift the chill of its grey surface. The vast unbroken expanse made for a harsh exterior, unalleviated by the few sandstone dressings which decorated the odd doorway or dormer. It did however display the simple lines employed in the design of the house, borne from a desire to distance this new generation of architecture from the “shams, inanities and affectations of the Victorian era”, as Nicoll states with just a hint of derision.

To my eye, roaming over the expressionless span of its walls, Balnowlart almost had a hint of the modern. Yet its design definitely heeds Nicoll’s warning against the dangers of “anglicising our buildings till we have forgotten our national style.” Balnowlart is most definitely of Scottish lineage; the massive walls, tall chimney stacks and hap-hazard arrangement of oddly shaped windows to the gable ends clearly channelling a more ancient aesthetic.

Coming to the north of the building I found myself amongst the old service wing, a neat single storey complex of small rooms forming a courtyard to the rear of the house. A collapsed motor garage accompanied the spaces necessary for the running of a fairly moderate residence, all succumbed to decay with some rooms missing their roofs entirely.

I passed through the former kitchen, the boards holding the old service bell mechanisms hanging limply against the peeling wall, and came to a small wooden staircase leading to the area above where no floor now remained. Years ago these would have carried a weary butler to his bedroom after a hard day’s work.

Now ready to enter the main house, I crossed the courtyard once more and slipped in through the back door. I had come into a dingy passage, still retaining its deep red painted walls, akin to some internal organ offering a bloody outpouring from its many wounds. Underfoot the floorboards were long gone, and I was left to pick my way through strewn debris and corroded water pipes below floor level.

This too was the servants’ realm, and I passed the gun room as I followed the corridor leading through the house. Balnowlart had been built originally for a wealthy Edinburgh family and was used sporadically as a holiday residence. I’ve heard say that the servants hated their visits to rural Ayrshire, being better accustomed to urban life, and would purposefully leave all the taps in the house running so as to use up the limited water supply and ensure a quick return to the city.

Reaching a doorway, I ducked behind a large section of laths which had slipped from the wall above, and entered the room beyond. I found myself in a hollowed out chasm, rising through the full three storeys of the house to offer views of the joists high above. I craned my neck as I gazed up towards the patches of sky visible through the roof, the structure still present but offering no protection to the sunken interiors within.

Above me, shards of the upper floors still clung to the perimeter of the walls, and a battered door opened into thin air. Through the many cracks and cavities, the afternoon sun diffused and cast strings of beautifully soft light across the stained plaster and hovering fireplaces. The atmosphere of this interior was potent; the edges gradually blurring as more and more of the fabric erodes, a visible record of dereliction’s rampant progress.

Retracing my steps down the passage I emerged into the main hall which ran through the centre of the building. The space was submerged in a chaos of detritus, and a large section of slated roof seemed to have found its new home here at ground floor level. I moved through the hallway, seeing where the staircase had once been, now nothing more than a ghostly impression rising to nowhere.

I came to another doorway, this time giving access to the slumped dining room, the only family room which had been located on this level. Standing at a precipice I regarded the room beyond, the cellars below having swallowed the entire floor. The remains of dull polished yellow pine panelling still braced the fragmented walls, and once again an incredible view was afforded through to the rafters.

I was struck by all the different layers which were becoming apparent as Balnowlart deteriorated, and thought how the last people to have seen it in a similar state were those who built it a hundred years previously. All of this would have been unseen by the people who spent their lives here, never knowing what lay beneath the skin of the place they called home. Now it is once more becoming plain to see as the house returns to the earth.

Preparing to take my leave, I stopped as I noticed a narrow path of rubble still gripping the very edge of the wall to my left. After a moment’s deliberation I decided to follow it, eager to see as much of the house as possible. I navigated some fallen beams and was led to a tiny void concealed behind the vanished staircase, linking the dining room with the servery.

Here I looked out through one of the house’s smallest windows, still with its wooden frame and a few shards of shattered glass. The valley stretched out beyond, a patchwork of pale greens as it slowly awoke, and I wondered who might last have gazed at this view, largely unchanged over the decades while the house around me suffered so much destruction.

A few minutes later and I was at the front door, snatching a final glance of the disintegrating hallway. Much of Balnowlart’s past remains a mystery to me. It is said to have played host to evacuated children during the war, but I have not yet discovered exactly when or why it was abandoned.

My mind turned to thoughts of who may have been the last one here, the last one to close the door, attempting to secure the house against what now devours it. As I exited through the open doorway something then caught my eye. On the flaking wood scrawled in red was written, eerily, yet quite suitably, one single word. BYE.

Special thanks to Stephen Ogston of www.ballantrae.org.uk for allowing me to include the historic photograph of Balnowlart in this post.